Steve McCurry è un fotoreporter, non un artista. Per fortuna.

Se lo fosse, le sue fotografie rischierebbero di nascere da una volontà retorica un po’ indigesta. Cioè, un conto è voler fare il ritratto fotografico a una piccola afghana in un campo profughi del Pakistan, altro è finire per farle un ritratto fotografico perché non ci si può sottrarre alla sua vista: agire senza ideazione preliminare.

Certo, poi lo sguardo, pur simbiotico con l’obiettivo della macchina, non può dimenticare la pittura, e allora capita che ai toni di verde degli occhi e delle veste che emerge dagli strappi del velo rosso si aggiunga il verde dello sfondo, e che la ragazzina sia di tre quarti con lo sguardo sgranato su chi la fotografa. La storia dei ritratti pittorici è ineludibile per chi si sia educato all’immagine, e a tratti sotto la pelle di Steve McCurry si avvertono – fusi e tradotti in altro ancora – il puntiglio fiammingo di Jan van Eyck e l’iperrealismo di Chuck Close.

Così come nell’ovale di un’Etiope, del 2014, si legge il nitore geometrico delle Madonne di Piero della Francesca, con il sapore ieratico dell’oro su una guancia e memorie del dripping di Pollock sull’altra.

Fatto sta che, benché arte non sia, la fotografia della bimba afghana, scattata nel 1984 e divenuta la copertina più famosa del «National Geographic», è quasi famosa come la Gioconda di Leonardo, e non credo sia solo perché riassume in sé le sofferenze del popolo afghano, come da più parti si dice. Di quello scatto colpisce, piuttosto, l’intensità di una bellezza altra. Colpisce la diversità rispetto a chi osserva. Non a caso le “icone” di maggior forza sono state immortalate da McCurry in paesi asiatici e africani. Lì McCurry si è trasformato in un raccoglitore di immagini, anzi uno spigolatore, un glaneur.

Immagine: Steve McCurry, Peshawar, Pakistan, 1984 © Steve McCurry

Ma è appunto andato, tornato e ritornato ascoltando il richiamo della diversità nel confronto con il mondo occidentale a cui egli appartiene. Al punto che anche il volto mirabilmente inespressivo di Robert de Niro, fotografato a New York nel 2010, arretra, se accostato a qualsiasi altra testa anonima emersa da luoghi per natura e per cultura dissimili dagli States.

E però proprio questo sembra il senso dell’operare di McCurry, la ricerca dell’altro da sé, che risulta oltremodo vitale in un momento storico in cui lo scatto fotografico, per di più dozzinale, non fa che ripetersi entro i margini claustrofobici dell’autoritratto.

Le icone di McCurry sembrano infatti idoli irraggiungibili, con una sacralità inviolata negli occhi, a dispetto di un corpo invece segnato da deprivazioni. Quasi un’implicita relazione chiastica con l’Occidente patinato, che di sacro non sembra avere più nulla.

Immagine:Steve McCurry, Lago Inle, Birmania, 2011 © Steve McCurry

Guardando le fotografie di Steve McCurry si ha anche la sensazione che il nocciolo della vita sia là, tra semplicità e miseria, e vien voglia di mettersi in viaggio per provare a cercarlo. Se non il nocciolo della vita, almeno certa sua intensità poetica che ci piace immaginare meta dei nostri passi, benché poi i nostri passi seguitino a muoversi in spazi di globalizzazione.

Allora si scopre un aspetto ulteriore della fotografia di McCurry, che è anzitutto testimonianza, ma ha anche un aspetto catartico.

Le ferite della storia sono esibite, ma come ricomposte in perfezioni formali di cui si fanno partecipi anche le rughe eventuali o i difetti fisici. Questo non per ricercati preziosismi, non c’è tempo per quelli, nel lavoro di McCurry i momenti sono più spesso da cogliere nel loro farsi che non da costruire.

C’è semmai, nel suo spigolare, lo stupore per la bellezza inattesa delle spighe non ancora raccolte.

Traduzione di Bertie Vitry

Steve McCurry is a photojournalist, not an artist. Luckily.

If he were, his photographs would risk being born from a slightly undigested and rhetorical desire. Namely, it is one thing wanting to capture a portrait of a little Afghan girl in a refugee camp; something else to take a photograph of her because you can’t avoid her gaze: acting without prior ideation.

Then, there is that look, even though it is symbiotic with the camera lens, it cannot ignore the painted form.

Therefore, the green of the background is layered onto the green of her eyes and clothing, tones that emerge from the folds of the red cloak;

the girl is taken from a three-quarter angle with her gaze fixed on the photographer. The history of pictorial portraits is unmissable for those steeped in art and, at times, underlying Steve McCurry’s work – blended and translated into something else – is the Flemish obstinacy for detail of Jan van Eyck and the hyper-realism of Chuck Close.

Similarly, in the oval face of an Ethiopian woman, from 2014, one can read the geometrical precision of Piero della Francesca’s Madonna images, with the solemnity of the gold on one cheek and memories of Pollock’s dripping technique on the other.

The fact is, though it is not art, the photograph of the Afghan child, taken in 1984 and that went on to become National Geographic’s most famous cover image, is almost as well-known as Leonardo’s Gioconda. I do not believe that this is solely because it captures the suffering of the Afghan population, as is often claimed. What is striking about the image is, instead, the intensity of such uncommon beauty.

What hits home is the difference between the subject and the observer. It is no coincidence that these ‘icons’ were shot by McCurry in African or Asian countries. There, McCurry is transformed into the capturer of images, or better, a gatherer of details; a gleaner. However, he has gone away, returned home, and gone away again, acting on the call of the difference from the western world to which he belongs. So much so that even the marvellously inexpressive gaze of Robert de Niro, photographed in New York in 2010, fades somewhat when considered alongside any anonymous figure from somewhere other than the United States, be it an otherness in terms of nature or culture.

It is precisely this that seems to inform McCurry’s work: the search for the other. This seems particularly pertinent in a historical period in which photographic images, usually run-of-the-mill, are repeated within the claustrophobic borders of self-portraiture.

Indeed, McCurry’s iconic images seem unattainable, with an unviolated godliness in their eyes in complete contrast to bodies that bear signs of deprivation. This is almost an implicit chiastic relationship with the glossy West, where most things sacred have been lost.

Observing the photographs of Steve McCurry, one has the sense that they convey something of the core meaning of life, lying between simplicity and misery. One has the urge to take a voyage to try to discover more about this meaning. If not something crucial of life, then at least the poetic intensity that we like to imagine as the ultimate destination of our journey, although we continue to exist in globalized spaces.

This leads to another feature of McCurry’s photography, which is foremost a testimony but also cathartic.

The wounds of history are on show but recomposed in perfect formality that includes the subjects’ wrinkles and physical defects. This is not due to any deliberate, formal refinement – there is no time for that in McCurry’s work where instances are more often captured than constructed.

There is, rather, in this gleaning, an amazement for the unexpected beauty of each single gaze still to be captured.

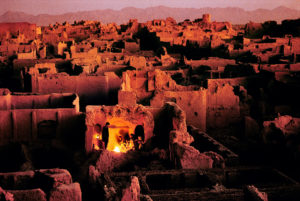

Immagine di apertura: Steve McCurry, Peshawar, Pakistan, 1984 © Steve McCurry